From the book, George Bowen of Bombay, “The White Yogi” by the Rev. J. Sumner Stone, M. D., Dec. 23, 1889:

Two young men just landed from America on “India’s coral strand” started out to see the curiosities and celebrities of a great city on the shore of the Indian Ocean. There were monuments, temples, and palaces by the score; there were princes and princelings, governors and generals and nabobs. But this morning we were hunting a prince, but not among palaces. So we picked our way through the crowded native district till we came to a broad street called Grant Road, and stopped in front of a low, one˗storied building divided into narrow apartments, two rooms deep. This was the office of the Bombay Guardian and the home of its editor and proprietor—one of the celebrities of India.

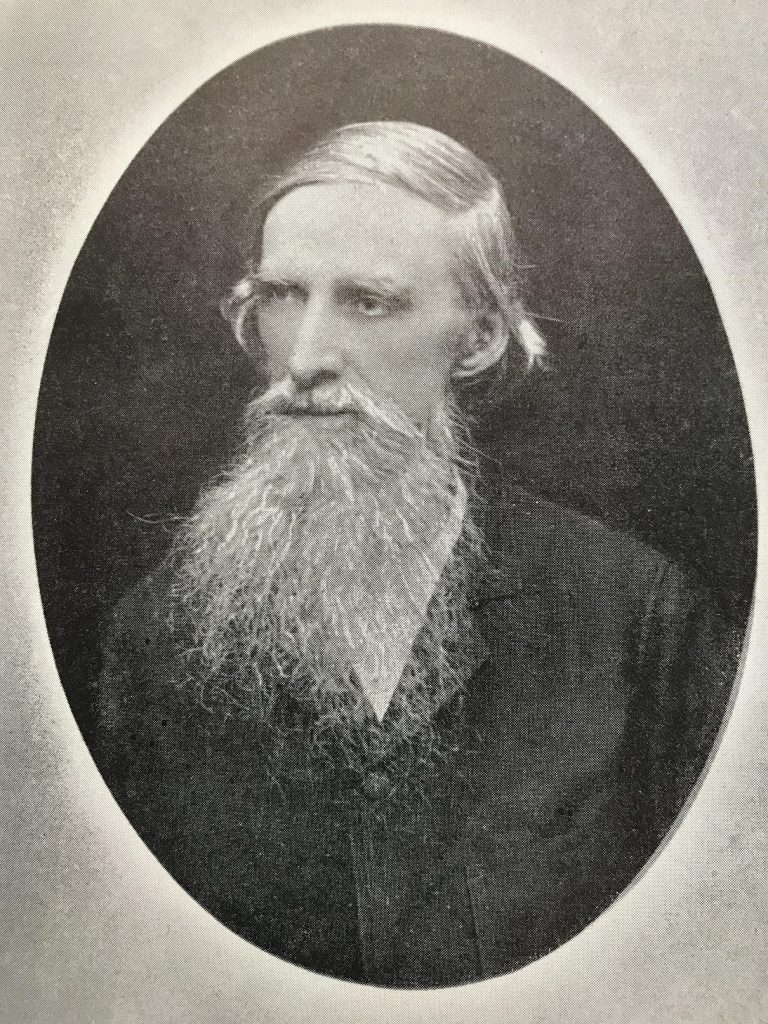

Americans and English called him George Bowen; natives called him the “White Yogi,” or white saint. To our timid knock the door opened and—I started. It was December, 1880, yet we seemed to be in the presence of a Huguenot, Geneva Calvinist, or Scotch Covenanter of the sixteenth century. The figure that greeted us might have been John Calvin or John Knox. Spare body, thin face, gray beard, narrow, high forehead, surmounted by rimless skull cap, thus the “White Yogi” stood framed in the door, bidding the strangers to enter.

How shall I picture to you that room? It was small, its furniture was of the plainest type and limited. The editorial table was a chaos of books, copy, manuscripts, and periodicals. Among the books, placed without order in the bookcases, I noticed a loaf of bread next to a dictionary, and a few bananas sharing a shelf with some works on theology and sociology. I realized that I was in the presence of a remarkable man, in the sanctum of one of the leading writers of the Indian empire, one of the most distinguished representatives of Christianity in the eastern world. At once there flashed into my mind the words of Jesus concerning John the Baptist: “What went ye out into the wilderness to see? A man clothed in soft raiment? behold, they that wear soft clothing are in kings’ houses. But what went ye out for to see? A prophet? yes, I say unto you, and more than a prophet.”

George Bowen was a scholarly man; he was by birth and training a gentleman. He was widely read, widely traveled, a thoroughly trained man. When he wrote golden words flowed from his pen; gems of thought fell from his lips when he spoke. He had the brain of a philosopher, the soul of a poet, and the genius of a musician. I wish I could convey to you the impression produced by the strangely˗gifted man when he sat down at the organ to let his fingers “wander idly over the noisy keys.” He lived in poverty, yet he was rich—he had all that the millionaire possesses—sufficient. He lived among the poorest of the people, was a comrade of the coolie, yet he was sought by the cultured and the noble.